Business Articles - Specialty and Trade

Articles & Tips

Some of the most appealing interior spaces are those created under a roof that has been sensitively fitted with dormers. Nestled at treetop level, these spaces are formed by the sloped, sheltering surfaces of the primary roof and the walls of the dormers, which admit daylight.

Adding dormers to a roof to meet space requirements has the advantage of keeping the primary roofline lower than would be possible with an additional full story. This can reduce the apparent mass of the building and help ground the home to the landscape.

Whether you're retrofitting dormers or including them in a new home, there are a number of design considerations to keep in mind. In order to create dormers that are both functional and a visual asset inside and out, you need to choose an appropriate dormer that's properly scaled and located. Dormers incorporated merely for a picturesque effect or to crudely maximize habitable floor space often fail to meet these criteria and may seem inauthentic. Successful dormers add pleasant living space while harmonizing with the overall building elevation and massing.

Dormer Types

There are three basic types of dormer, described by the dormer's relationship

to the primary roof: built-out dormers, which are the most prevalent; partially

built-out/partially cut-in dormers, which are less common; and cut-in dormers,

which are fairly rare. Built-out dormers can be further characterized as either

fully or partially nested within the primary sloped roof. A fully nested dormer

is completely encompassed by the primary roof, since it sits some distance above

the primary eaves line, which is continuous. A partially nested dormer is created

by extending the exterior wall plane of the main building vertically to form

the wall of the dormer, thereby interrupting the primary roof eaves line.

The variety of roof types found in primary roofs can also be found in built-out and partially built-out dormers. In general, it's best to select a dormer roof type that's compatible with the primary roof. This doesn't mean it has to be the same roof type, but it should relate to the style or vernacular of the building as a whole. It's best to narrow your selection of dormer types used in any one roof: Too many different dormer types will create an unfortunate muddled jumble.

Dormer Placement and Scale

Placing dormers is about achieving balance and texture on the exterior while

satisfying interior space requirements. A blocklike symmetrical building may

invite somewhat methodical dormer placement; window and door locations on the

walls below generally guide dormer locations above. In this scenario, multiple

single dormers may enliven the roofscape, staccato fashion, while softening the

building's apparent mass.

By contrast, a longer, asymmetrical building may allow for more flexible dormer placement. If you're no longer restrained by the strict rules of symmetry, you can place combinations of continuous and non-continuous dormers to complement or counterbalance a more rambling footprint. Dormers can be used to highlight the horizontal line of the building or to create a local symmetry that enhances the elevation.

When placing dormers, pay attention to the hierarchy of forms. Dormers that are out of scale with the rest of the house may appear overwhelming and no longer secondary to the primary roof. In the other extreme, dormers that are too small may appear lost within the roofscape, and more of a blemish than a benefit. Use dormer placement and scale to enhance and clarify building function and massing.

Continuous Shed Dormer

The shed dormer is a versatile option. When elongated, as shown at right, it's

a good choice for continuous headroom and maximum daylight. Though sizable,

this dormer is comfortably nested within the main roof thanks to the entry extension,

the slight setback from the lower wall, and the fact that it doesn't extend the

full length of the house. Also, the dormer window size and style relate well

to the windows on the rest of the house.

An Unfortunate Dormer

Here, interior space has been maximized at the expense of exterior massing

and charm. Because the shed dormer isn't subordinate to the main roof, it creates

a towering, awkward three-story building. The sides of the dormer as well as

its face are in the same plane as the walls below, which partially accounts for

its unfortunate boxiness; the low slope of the dormer roof completes the boxy

effect.

A Varied Dormer

Here, three different dormer types — hip dormers, a shed dormer, and a partially

nested hip dormer — are all expertly balanced on the gambrel-roofed house.

Dividing what could have been a continuous shed dormer into separate distinct

entities reduces its mass and overall scale without sacrificing headroom or daylight.

The decision to terminate both ends of the dormer with hip roofs accomplishes

a couple of things: For one, it helps keep the dormer subordinate to the main

roof, since the hip roof cheek walls consume less area than those of a shed dormer.

Second, the hip roofs slope back toward the center, which further distinguishes

the hip ends from the linking middle section of roof. This allows the observer

to "read" distinct rooms within: bedroom, hall, bedroom, for example, or bedroom,

hall, bath.

The separate partially nested hip dormer is formed by extending the exterior

wall plane up through an interrupted eaves line. This dormer's placement, roof,

and window configuration reflect the neighboring fully nested dormers, helping

it to fit in and to tie together the overall elevation.

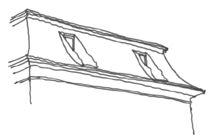

Mansard With Partially Cut-In Doghouse Dormers

This mansard-roofed house is punctuated with discreet non-continuous gable dormers.

Due to the fairly steep slope of the lower portion of the mansard, these dormers

are less about gaining headroom and more about introducing daylight with style.

Since the overall building is symmetrical, the dormers are symmetrically placed

too. These dormers are partially built out from the main roof and partially cut

in. If they had been entirely built out, the windows would have been moved out

farther toward the exterior. This would have resulted in large, exposed cheek

walls, and the dormers would have appeared bug-eyed. By cutting them in partially,

that problem is alleviated.

Fully Cut-In Dormers

If the dormers above had been

fully cut in, as here, they would have still admitted daylight, though less than

in the example above due to shadows from the cheek walls. The fully cut-in dormers

appear oddly contemporary for such a classic house. The cutouts suggest skylights

more than dormers; plus, there's no headroom gain. These simply lack charm.

Built-Out Doghouse Dormers

Small, fully nested gable dormers on either side of a central, larger gable element

provide a fair amount of headroom and daylight to this attic. The dormers are

located in logical relationship to the windows and volumes below, contributing

to a hierarchy of base, middle, cap. They also help to break up the mass of what

is otherwise a blocklike building, much like the mansard example at top.

Eyebrow Dormer

The eyebrow dormer is a classic shingle-style feature. As in this example, it

is traditionally a small curved-topped element folded into the roof much the

way our eyes are folded into eyelids and brows. It provides a peekaboo of light

and ventilation. It is not the right choice if your objective is to gain significant

headroom. It is a quiet, beloved detail.

Gable Dormer, No Cheeks

This gable dormer, which has no sidewalls, is a great counterpoint to the gable

roof on the ell of the main volume. Had this been a doghouse dormer instead,

it might have looked slightly isolated within the length of the roof. It would

have become more of a "mini me" than its current incarnation, which is more like

a sibling or mate to the ell gable.

Barrel-Shaped Dormer

These elegant barrel-shaped dormers provide dynamic sculptural relief to the

otherwise severe blocklike massing of this building. They may well play a more

important role on the exterior elevations of this building than as functional

devices to add headroom and daylight to the attic.

Katie Hutchison is an architect and owner of Earthlight Design in Salem, Mass.

This article has been provided by www.jlconline.com. JLC-Online is produced by the editors and publishers of The Journal of Light Construction, a monthly magazine serving residential and light-commercial builders, remodelers, designers, and other trade professionals.

Join our Network

Connect with customers looking to do your most profitable projects in the areas you like to work.